In Austria, according to recent epidemiological estimates, around 115,000 to 130,000 people live with some form of dementia. As a result of increasing life expectancy, overweight, diabetes, and age-associated cardiovascular complications, the number of people at increased risk of dementia—and consequently the number of those affected by dementia—is continuously rising. Unless a breakthrough in prevention and therapy is achieved, various projections of population development suggest that the number of people with dementia will roughly double by the year 2050.

Spermidine is a natural substance derived from amino acid metabolism, found in all living cells and organisms, and its concentration generally decreases with age. Systemic spermidine levels are maintained by three sources: dietary intake, the gut microbiome, and cellular biosynthesis (originating from the amino acid arginine).

Spermidine has been described as a so-called caloric restriction mimetic, meaning that external supplementation mimics certain aspects and cellular processes of fasting. An important cellular process initiated in this context is so-called autophagy (from the Greek for “self-eating”), a kind of molecular recycling mechanism that is activated during periods of nutrient deprivation to overcome energy crises. During autophagy, cellular components that are dispensable for the immediate function of the cell—such as fats, mitochondria, and aggregated proteins—are digested in the lysosome and broken down into reusable units. This process also breaks down cellular “waste dumps” (such as aggregated proteins or defective mitochondria), which in aging can contribute to neurodegeneration and other (cellular) dysfunctions.

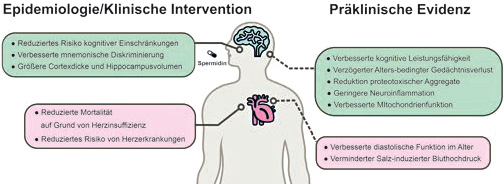

Spermidine Supplementation Delays Cardiac Aging

Research as early as 2016 demonstrated a cardioprotective effect of a spermidine-rich diet (Eisenberg et al., 2016; Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nature Medicine, 22(12): 1428–1438. doi: 10.1038/nm.4222). In animal models, spermidine supplementation (added to drinking water) was shown to delay cardiac aging and reduce salt-induced hypertension. Supporting data were also observed in an epidemiological human cohort study: higher dietary spermidine correlated directly with a lower risk of heart failure, fewer cardiovascular diseases, and a reduced incidence of death due to heart failure (Bruneck Study).

Building on these age-protective and autophagy-promoting properties of spermidine, the potential neuroprotective effects of spermidine have come into focus in recent years of spermidine research. Sigrist and colleagues demonstrated in a groundbreaking publication that (Gupta et al., 2013; Restoring polyamines protects from age-induced memory impairment in an autophagy-dependent manner).

Spermidine is a

natural substance

derived from

amino acid metabolism,

found in all living

cells and organisms.

Nature Neuroscience. 16(10): 1453–1460. doi: 10.1038/nn.3512.), that in fruit flies, an age-related decline in cognitive performance—similar to that observed in humans—can be halted through spermidine supplementation. This improvement in memory function through spermidine was accompanied by an autophagy-mediated reduction of aggregated proteins in the brains of the flies. Autophagy was necessary for the spermidine-induced improvement of cognitive function in aged flies.

Reduction of Neuroinflammation

A number of subsequent publications have confirmed these findings in rodents. For example, Filfan and colleagues showed that lifelong supplementation of rats with spermidine reduced neuroinflammation, while various aspects of learning, such as exploratory behavior, were improved. (Filfan et al., 2020; Long-term treatment with spermidine increases health span of middle-aged Sprague-Dawley male rats. GeroScience. doi: 10.1007/ s11357-020-00173-5). Another study demonstrated in a genetically fast-aging mouse cohort that spermidine supplementation minimized brain aging as well as behavioral aspects of aging. (Xu et al.; 2020; Spermidine and spermine delay brain aging by inducing autophagy in SAMP8 mice. Aging. doi: 10.18632/aging.103035).

De Risi and colleagues were able to show that transgenic mice suffering from mild dementia exhibited improved memory function and a lower amount of proteotoxic aggregates in the brain when fed spermidine (De Risi et al.; 2019; Mechanisms by which autophagy regulates memory capacity in ageing. Aging Cell. n/a(n/a): e13189. doi: 10.1111/acel.13189).

Recently, Madeo, Sigrist, and Eisenberg demonstrated in two publications that dietary spermidine actually reaches the brains of mice, thereby crossing the blood-brain barrier. (Schroeder et al.; 2021; Dietary spermidine improves cognitive function. Cell Reports. 35(2): 108985. doi: 10.1016/j. celrep.2021.108985; Liang Y, et al., 2021; eIF5A hypusination, boosted by dietary spermidine, protects from premature brain aging and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Reports. 35(2): 108941. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep. 2021.108941). Here too, the mice exhibited improved memory function in old age, along with modification of a key protein translation factor (EIF5A in the hippocampus, a critical node between short-term and long-term memory). This biochemical modification (also known as hypusination) as well as mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) were shown to be causal for the improvement of memory function by spermidine in aging flies.

The dementia-protective

potential of spermidine

was recently demonstrated by

another

confirmed by another pilot study.

Evidence in humans

The now very solid preclinical evidence for spermidine as a neuroprotective molecule during ageing is being joined by more and more human studies. In an epidemiological study, Stefan Kiechl from the Medical University of Innsbruck, together with Madeo and Eisenberg, demonstrated a correlation between the amount of dietary spermidine intake and memory function. A randomized clinical pilot study conducted by Charité in Berlin (the preSMARTAGE study) also demonstrated an improvement in memory function through spermidine supplementation. Three months after taking a spermidine-rich wheat germ extract, participants who reported a self-perceived, but not yet clinically manifest, decline in memory function showed an increased score on the so-called “mnemonic discrimination test.” This is a cognitive performance test that assesses the ability to discriminate and recognize similar images (Wirth et al., 2018; The effect of spermidine on memory performance in older adults at risk for dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Cortex, 109: 181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2018.09.014). Higher spermidine intake was correlated with increased hippocampal volume and greater cortical thickness (Schwarz et al., 2020; Spermidine intake is associated with cortical thickness and hippocampal volume in older adults. NeuroImage, 221: 117132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117132). The dementia-protective potential of spermidine was recently confirmed by a further three-month multicenter pilot study in Styria/Austria (Pekar et al., 2021; The positive effect of spermidine in older adults suffering from dementia. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 133(9): 484-491. doi: 10.1007/s00508-020-01758-y).

Based on these scientific findings, spermidine is considered a promising natural and endogenous substance for reducing the risk of developing dementia and should be further investigated in larger multicenter clinical studies.